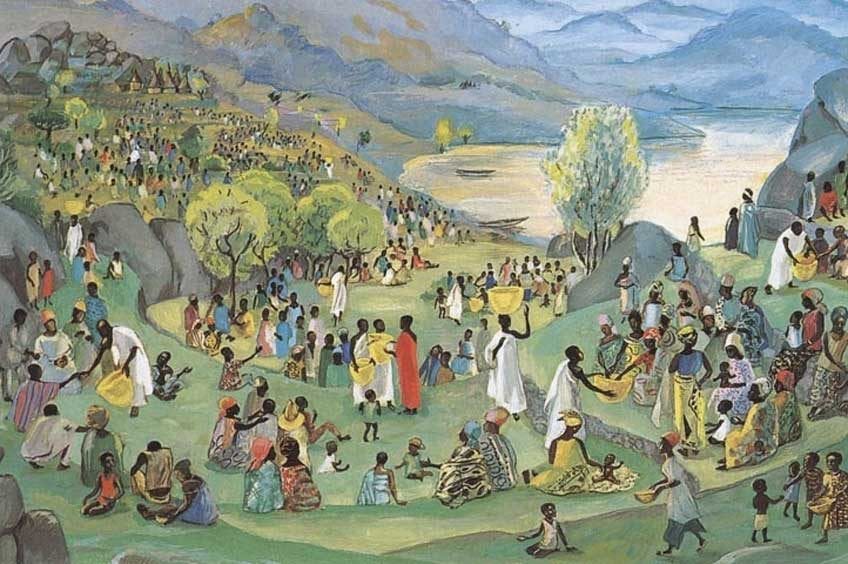

And Jesus went throughout all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every affliction. When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Then he said to his disciples, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore pray earnestly to the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.”

SCALE!!

Scale is the glory of the Internet age. Scale mints billionaires, turning college dropouts into the world’s rich new elites.

Scale amplifies the clever, helping the brashest marketers blow their average counterparts out of the water.

And scale plants its seed in our hearts, promising that we, too, are but a step away from fame & fortune.

It’s striking how differently Jesus’s revolution worked.

Sure, there were times he reached thousands—the Sermon on the Mount, the feeding of the hungry crowds. But more often, Jesus worked one on one, as these essays have often emphasized. Talking with my friends Rick, Colten, & Roland the other night, Colten mentioned the Japanese theologian Kosuke Koyama’s idea that Christians worship a “three mile per hour God”—that is, Jesus operates at the speed of walking, journeying from town to town on foot, often accompanying others on their own journeys.

That pace drives us crazy now. Our goal is to be light-speed people; the speed of a virus’s spread is our ideal.

Yet Jesus’s 3 m.p.h. pace changed the world. How did such a thing happen?

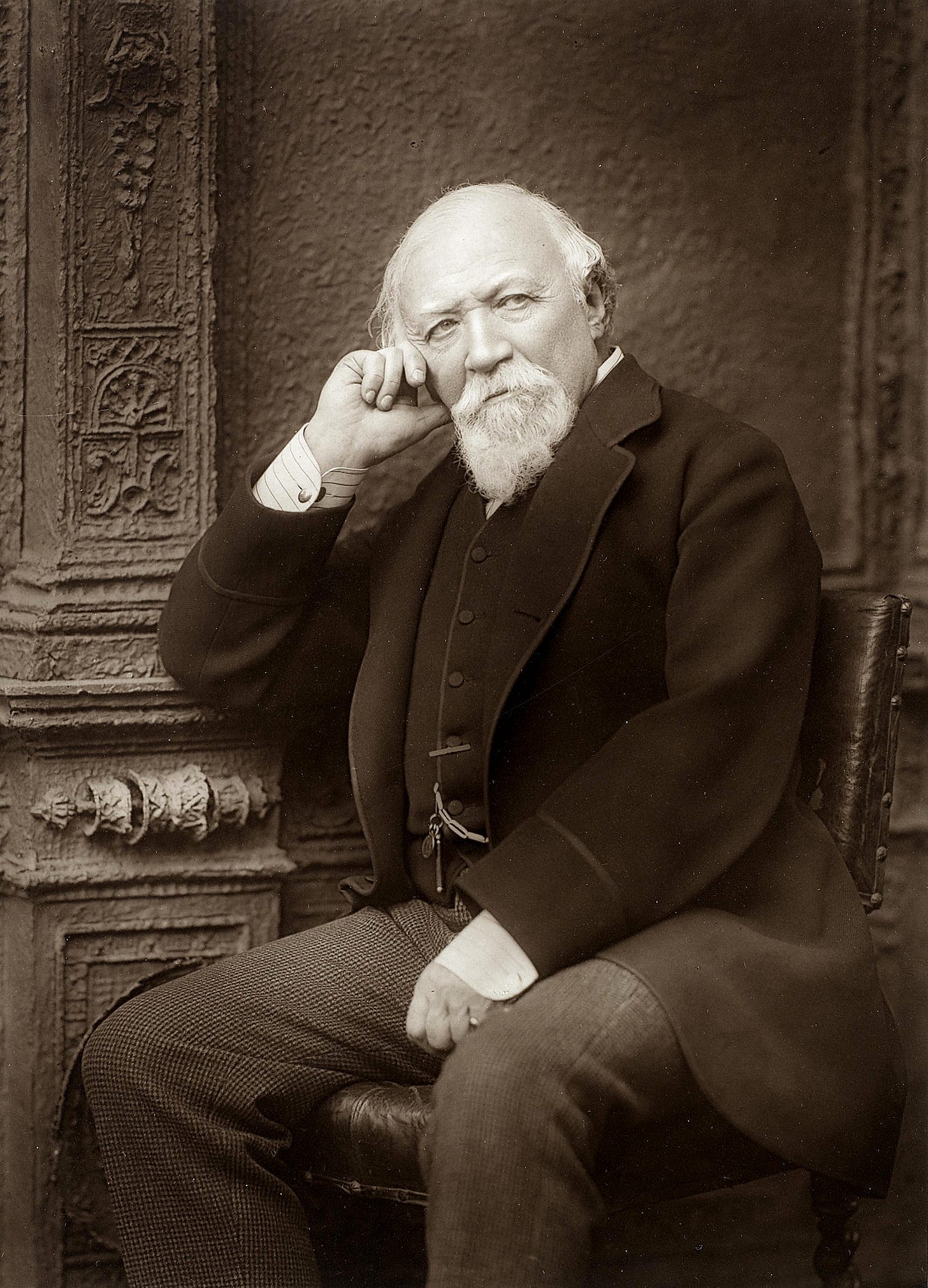

Karshish, the Arab Physician

If you have a few minutes to spare, read Robert Browning’s strange poem “An Epistle Concerning the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish, the Arab Physician.”

In the poem, Browning imagines a physician named Karshish traveling through Palestine in the first century AD. Karshish is a sort of proto-Muslim, devout, seeking out “God's handiwork” as revealed through science. The poem takes the form of a letter that Karshish writes to his friend and fellow physician—one scientist writing to another.

Karshish explains his encounter with a strange man named Lazarus—and winds up reveal how deeply unsettled he is by the encounter. Lazarus doesn’t preach from the street corner. He’s not out to make converts. He simply doesn’t care if Karshish or anyone else believes his story of how, three days after he died, Jesus “bade him ‘Rise’ and he did rise.” Ever since his resurrection, he lives in a state of absolute indifference to the things most people care about—riches, appearances, geopolitics. Instead,

Contrariwise, he loves both old and young, Able and weak, affects the very brutes And birds—how say I? flowers of the field.— As a wise workman recognizes tools In a master's workshop, loving what they make.

Karshish can’t accept Lazarus’s explanation for his life, nor the idea of the incarnation upon which it rests.

But Karshish keeps returning to the strange power of the story he’s been told, embarrassing though it is for him to admit it. His mind and imagination have been transformed by the encounter, and he can’t shake the powerful conclusion of Lazarus’s simple story:

The very God! think, Abib; dost thou think? So the All-Great, were the All-Loving too— So, through teh thunder comes a human voice Saving, "O heart I made, a heart beats here! Face, my hands fashioned, see it in myself! Thou hast no power nor mayst conceive of mine, But love I gave thee, with myself to love, And thou must love me who have died for thee!" The madman saith He said so: it is strange.

Jesus didn’t use the mechanisms of empire to spread his message (though his later follower Paul wasn’t averse to doing so). Instead, he suggested a more profound truth: life’s value can’t be measured by “productivity” or any other measurable, quantifiable method.

So, this message spreads to his friend Lazarus… then to Karshish… then to Abib. And now, a hundred and fifty years later, from Jesus and Lazarus via Browning to us.

It’s not exactly efficient.

But everything that scale says is valuable, Jesus suggests is worthless. Scale misses the most important things—the blade of grass, the light on a bird’s wing, the delightful weirdness of the people around us. Miss these things, and we’ve missed it all.

As Paul Kingsnorth recently wrote, “Put the peace of the heart before everything.”

Or, as Jesus teaches us here, harvest just the single stalk of wheat before you.

We can remind each other not to live as if we were called to use industrial machinery to interact with each other, but with singular attention, attention that helps bring into focus the wholeness and uniqueness of the few people nearest us.

Sure, doing so isn’t efficient. But that’s exactly why so many workers are required for this harvest!

As another Victorian poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, wrote (thanks again, Colten, for calling this passage to mind):

For Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men's faces.Apologies for the absence of posts this summer. It’s been a busy one! Hopefully I’ll get back to a normal writing pace this fall.