What does it mean to have authority?

Reflections on the good teacher at the end of the Sermon on the Mount

And when Jesus finished these sayings, the crowds were astonished at his teaching, for he was teaching them as one who had authority, and not as their scribes.

~Matthew 7:28–29

Our culture is obsessed with dichotomies: we divide teaching from doing, theory from practice. Maybe you’ve heard the line that goes something like “Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.”

The phrase is intended to insult teachers. But five seconds’ thought reveals that it’s silly. Think about the best teachers you ever had. What were they like?

They probably had integrity. Energy. Enthusiasm. A clear sense of direction. Expertise. Kindness.

You can’t be a great teacher without the ability to do a huge range of things very well. Conversely, plenty of people can do many things, without doing any of them well.

So what exactly is the connection between thinking, teaching, and doing?

Today we come to the end of the Sermon on the Mount—the collection of Jesus’s teachings that have been the focus of these essays since November.

This collection ends with a passage that asks us to consider what it actually means to be a good teacher—a remarkable sentence describing the crowd’s reaction:

And when Jesus finished these sayings, the crowds were astonished at his teaching, for he was teaching them as one who had authority, and not as their scribes.

Frankly, the passage describes my own reaction, too, after having reflected on the Sermon on the Mount for the past few months in these essays. These teachings still have an authority that continues to resonate, even thousands of years later.

There’s a contrast drawn here between how Jesus teaches and how the scribes and pharisees teach. While it’s foolish to draw an overly simplistic line between teaching and doing, there is a difference, and it’s exactly what this passage gets at.

How did Jesus obtain this authority that astonished the crowds? It’s not like he had been teaching for decades: the Sermon on the Mount is presented as the first substantive teaching of Jesus’s ministry.

But if we look more broadly at Jesus’s life, we can see a spiral path that has three mutually reinforcing components, each of which is necessary for growth in wisdom & authority:

Thinking

Creating

Teaching

Each of these builds on the others: the best teachers are reflective makers. The best makers are also philosophers and mentors; the best philosophers are teachers who make and form—communities, schools, disciples.

All three are important, even necessary, aspects of human life that help us to better understand ourselves and one another. This spiral path is one we can follow to help us increase our own flourishing, and the flourishing of people around us.

Let’s trace out this spiral path in Jesus’s own life.

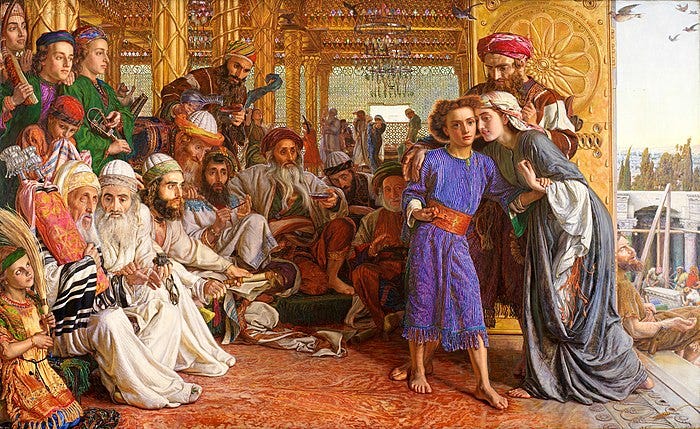

Thinking: Jesus at the temple

After three days [Jesus’s parents] found him in the temple, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions. And all who heard him were amazed at his understanding and his answers. . . . And Jesus increased in wisdom and in stature and in favor with God and man. (Luke 2:41–52)

Don’t think that you can or do skip this step, even if you think of yourself as “practical” rather than “philosophical” or “brainy.” To learn something, you have to have room for it in your mind. You make room for new things by connecting them to what you already know, raising questions, “wrapping your mind around” them.

On the other hand, you can’t just stay here at this step. Too often, this is what we do—getting into fights over minor details of doctrine or theory that are purely abstract. We analyze, then we over-analyze.

This sort of pure, abstract, philosophical thinking is critical. But it’s only the first step if we want to develop and grow.

Doing: Jesus as carpenter

As

has discussed in a great interview, Americans are prone to a paralyzing level of abstract over-thinking—and need to get building again to restore some dynamism to our economy.But this isn’t just an economic problem. It’s a problem of spiritual and moral purpose. We’re missing essential elements of life if we’re stuck in our own heads.

Consider: after the story of his childhood in the temple, Jesus entered his formative years of adolescence. For him, that included apprenticeship under his father as a carpenter—something we know from references such as these, combined with our historical knowledge of the period:

Is not this the carpenter's son? (Matthew 13:55)

and

Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon? (Mark 6:3)

It’s easy to gloss over this period in Jesus’s life, not least because the Gospel accounts themselves gloss over it. But I’d argue it was critical for Jesus in his transition from a brilliant thinker—a child prodigy, clearly—to a good teacher. And it’s a critical stage in our own development as flourishing humans, too.

When we’re doing and making, we take ownership over what we have learned theoretically. We make it our own. This is as true in our ethics as it is in more practical disciplines like carpentry. In fact, the practical disciplines themselves have an intrinsically moral component to them.

has written beautifully about this moral dimension, and how our culture has largely forgotten it, in his book Shop Class as Soul Craft. And there’s a great newsletter here by called that focuses specifically on these ideas.In short, the idea is that these trades and traditions train our abilities in the realm of practical judgment: taking ideas and transforming them into reality, with all the attendant difficulties that entails.

(Brief digression: it’s interesting that the Greek work used in the passages above, tekton, seems to mean something much broader than the very specific “carpenter.” It can mean carpenter, but also builder or even more broadly, craftsman.)

This is a long, frustrating, difficult process. But it’s essential for us all if we want to have authority: thinking without doing is just abstract theory. It might work if we’re content living in fantasies—but that won’t satisfy anyone for long.

For example, you can’t build a tree fort without applying your concept to the particularities of your landscape and the materials you have to work with. (An example that happens to be very relevant to my life this summer.)

Nor can you profess to live by an ethical system without nurturing the practical judgment necessary to apply it to your life everyday, in both the most humdrum circumstances and the most extreme.

In short, thinking is fulfilled by doing.

Guiding: Jesus the good teacher

But doing isn’t the end of the process. Even if you take the step from thinking to doing, you’re short-changing yourself and your community if you don’t take one final step: from maker to mentor.

In terms of Jesus’s life, this is right where we’ve been for most of the issues of this newsletter: exploring how Jesus’s teaching impacts us.

Teaching, guiding, mentoring, parenting—these are how we truly impact the world. Our creative endeavors are limited in scope. There’s a finite amount that we can create. But the impact of good teaching is nearly unlimited. Jesus was a provincial craftsman, but he changed the course of the world through the power of his teaching.

We started by rejecting the false dichotomy between teaching and doing, but insisting there is still a difference between the two. And, it turns out, teaching is really the fulfillment of doing—it’s creating and thinking, both raised to the next level by helping draw others in.

What about you?

Yet teaching isn’t simply the last stage in our development, either. Remember, this process is a spiral, not a line. Jesus continues thinking and doing even as he continues guiding and teaching. Many of the stories we’ll explore in coming weeks relate to what Jesus does and how he argues, as much as to what he teaches.

In the same way, I’d argue that we all need to continue working on each of these three areas if we want to live fulfilled lives, because reflective thinking improves our making and our teaching. Our creative pursuits make us better thinkers and teachers. And teaching helps us to better think and create, and helps make our thinking and creating more powerful.

So, do you agree that all three elements in this triad are critical for our flourishing?

Which areas come the most naturally to you?

Do you find yourself gravitating toward one or two of the three?

How could pushing yourself to add a second or third dimension to your life bring more flourishing—to you and to your neighbors?

This was really an excellent analysis (and not just because you gave me a shoutout: thank you kindly!). I was joking with some executives from our parent company just a couple mornings ago who were on site touring our academy and said, “Yeah, I couldn’t hack it in the field so I teach it in the class now.”

For years I’ve been smitten with the idea, one I grew up without, that Jesus actually learned things from His parents and labor. The cultivation of His virtue and His interior formation were in the context of worship wedded to work. You’ve done a wonderful job of illustrating this. And then touching on the source of His authority: the Pharisees taught from the words of wise men before them; Jesus taught as the Wise Word. The source of His authority is the Father, in one sense, and that’s always what I’ve heard, but it came from His *experience* of living the life to which the Scriptures pointed, something which the Pharisees had only in part or not at all.

Anyway. Great piece. Really thought provoking.

I love the distinction you’ve drawn up! Wouldn’t you say that learning can also directly relate to doing though, or do you specifically mean learning ethical things? If it’s just ethics, then I absolutely agree that living the ethics learned comes before teaching them.