A Tale of Two Sams

On the arrogant ignorance of Sam Bankman-Fried, Sam Altman, and their intellectual godfather Derek Parfit

Hello! Welcome to a new-ish series from The Good Teacher. These occasional posts, tagged More Human, will focus on core human truths in a world that worships antihuman values. Today’s essay is the second in the More Human series. The first was about building better social media.

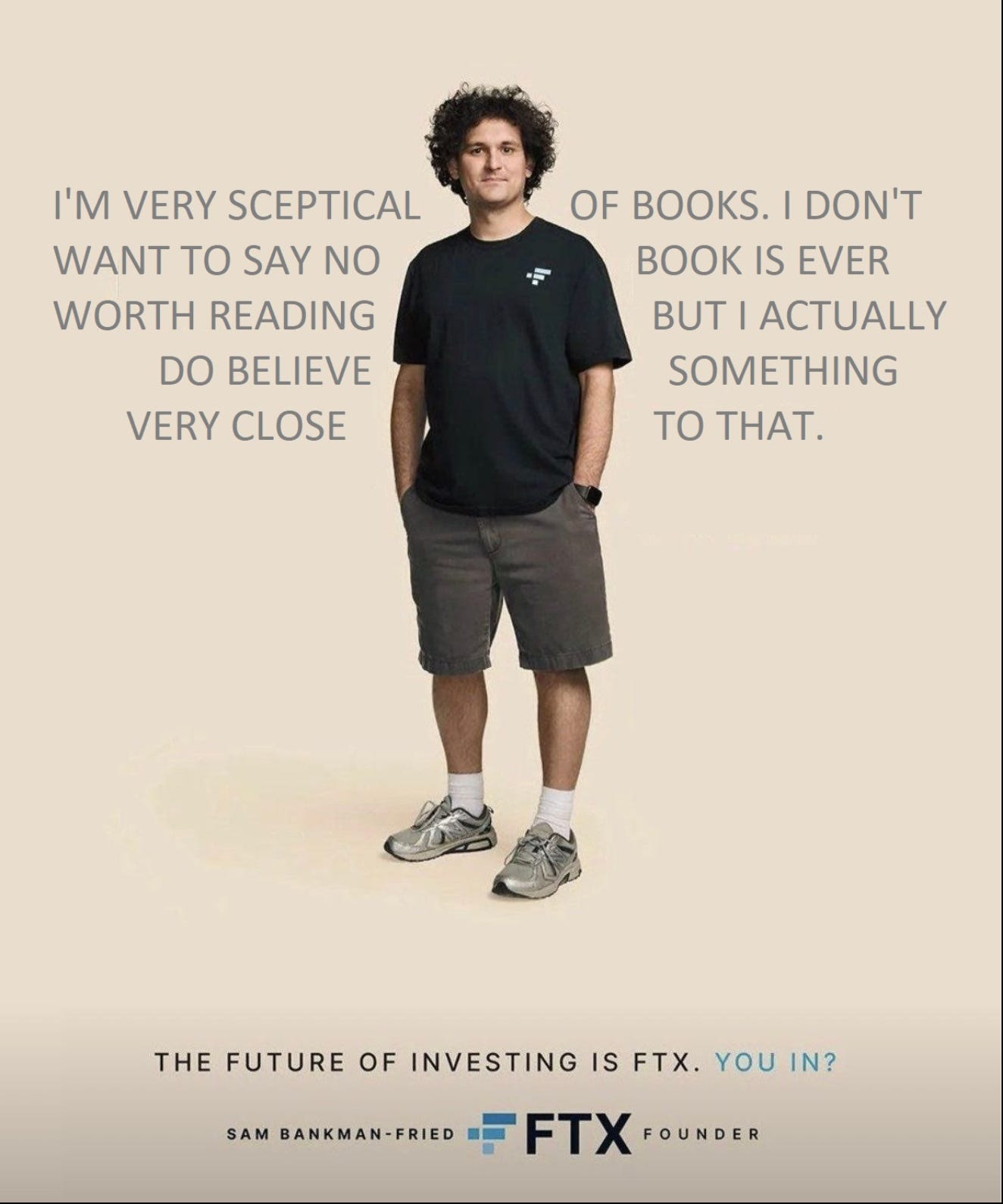

In utterly unsurprising news, Sam Bankman-Fried, the creator of a once-massive and now collapsed crypto-currency empire, was found guilty of fraud & conspiracy. SBF either didn’t understand the billion-dollar business he was running, or he did but he’s incredibly malicious, or he has the world’s worst memory, or all of the above.

Meanwhile, in very surprising news from earlier today, Sam Altman, the CEO of the meteoric AI startup OpenAI, was fired today. [Note: I started this post two weeks ago, before this news broke.]

Altman was, until today the media’s darling entrepreneur of the moment. (An awkward position, since the last person there was Bankman-Fried.) Altman’s been the subject of profiles in every significant newspaper or magazine: here’s The New Yorker and New York magazine, for starters, and the New York Times; Altman also got the multi-hour Lex Fridman treatment, too.

The two don’t just have a first name in common. In fact, after you’ve read a few profiles, the parallels between the two are eerie. For people with so much power, it’s not surprising that they’re both obviously smart in some basic sense; it’s that they’re so obviously deeply ignorant in many others. The weirdly specific traits these two men share tell us much about the world we’ve created, which their lives and companies have reinforced, despite both men’s downfalls.

Naïveté

Both men shared a level of cluelessness that could be absolutely stunning. Consider the following anecdote, from Elizabeth Weil’s exceptionally good profile in New York magazine [the italics are my own]:

In his office in August, Altman was still hitting his talking points. I asked him what he’d done in the past 24 hours. “So one of the things I was working on yesterday is: We’re trying to figure out if we can align an AI to a set of human values. We’ve made good progress there technically. There’s now a harder question: Okay, whose values?”

At [a conference where Altman was interviewed], the moderator pressed Altman: How did he plan to assign values to his AI?

One idea, Altman said, would be to gather up “as much of humanity as we can” and come to a global consensus. You know: Decide together that “these are the value systems to put in, these are the limits of what the system should never do.”

The audience grew quiet.

“Another thing I would take is for Jack” — Kornfield — “to just write down ten pages of ‘Here’s what the collective value should be, and here’s how we’ll have the system do that.’ That’d be pretty good.”

The audience got quieter still.

Meanwhile, in crypto-land, after Sam Bankman-Fried was in huge trouble for losing millions and millions of dollars in customer funds, did he clam up like a normal American corporate suit about to be arrested for fraud, realizing his every word was likely to further incriminate him?

No! He took to his Twitter DMs to pour out his heart to a journalist from Vox. His defense for losing vast quantities of customer money? Literally, “Sometimes life creeps up on you.”

This is why it’s not surprising that he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Sometimes life creeps up on you.

Narcissism

It’s much easier to live with this level of naïveté when you’re a narcissist. One of Bankman-Fried’s colleagues/co-conspirators/off-and-on lovers, Caroline Ellison, related the following anecdote to the New York Times:

Before his companies collapsed, Mr. Bankman-Fried often described himself as a utilitarian — meaning that he made decisions designed to advance the greater good. He told Ms. Ellison that “rules like ‘don’t lie’ or ‘don’t steal’” didn’t fit into that framework, she said. Over time, she explained, those beliefs started rubbing off on her. “It made me more willing to do things like lie or steal,” she said.

Forbes—in a worshipful profile—described him as:

a mercenary, dedicated to making as much money as possible (he doesn’t really care how) solely so he can give it away (he doesn’t really know to whom, or when).

And Ginia Bellafante, in another New York Times piece, this one with the delightful title “Sam Bankman-Fried was a grown-up criminal, not an impulsive man-child” (but are those really mutually exclusive?), describes how:

Held up against other notorious investors whose fate landed them in Lower Manhattan federal court, Mr. Bankman-Fried stands out particularly for [his] commitments to self-promotion. Michael Milken, known for his role in creating junk bonds in the 1980s and for the prison sentence on fraud and racketeering charges that followed, was an extremely private person who avoided publicity, as one is probably well-advised to do when taking up tax evasion.

You know you’ve taken a wrong turn in life when you make Bernie Madoff look good.

Sam Altman seems to have taken a page or two from SBF’s book, according to Weil:

By Altman’s own assessment — discernible in his many blog posts, podcasts, and video events — we should feel good but not great about him as our AI leader. As he understands himself, he’s a plenty-smart-but-not-genius “technology brother” with an Icarus streak and a few outlier traits. First, he possesses, he has said, “an absolutely delusional level of self-confidence.” Second, he commands a prophetic grasp of “the arc of technology and societal change on a long time horizon.” Third, as a Jew, he is both optimistic and expecting the worst. Fourth, he’s superb at assessing risk because his brain doesn’t get caught up in what other people think.

“An absolutely delusional level of self-confidence.” Whatever happened to the days of humble servant leadership?

Love of theoretical “humanity,” scorn for actual human beings

One of the most disturbing traits the two share is their love of theoretical humans, which is combined with scorn for real ones.

A New Yorker article that included a long section on SBF related:

One disaffected E.A. [effective altruist—a community of people with a bizarre view of ethics, as we’ll see later] worried that the “outside view” might be neglected in a community that felt increasingly insular. “I know E.A.s who no longer seek out the opinions or input of their colleagues at work, because they take themselves to have a higher I.Q.,” she said.

According to Bellafante, Bankman-Fried

worked 22 hours a day and submitted the prospect of any interaction with another person to a cost-benefit calculation that frequently left him canceling meetings and other obligations at the last minute, because, as Michael Lewis writes in “Going Infinite,” his book about Mr. Bankman-Fried’s rise and fall, “he had done some math in his head that proved that you weren’t worth the time.”

Along the same lines,

For Mr. Bankman-Fried, it was apparently fine to designate all people over 45 as “useless” and to look and sound like a 13-year-old boy even as he got to speak alongside Bill Clinton and Tony Blair.

You won’t be surprised to find that Altman has pretty much the same view of humans—maybe worse, actually:

Altman’s great strengths are clarity of thought and an intuitive grasp of complex systems. His great weakness is his utter lack of interest in ineffective people, which unfortunately includes most of us.

It’s not just that he’s uninterested, though. Weil reports that Altman

uses the phrase “median human,” as in, “For me, AGI” — artificial general intelligence — “is the equivalent of a median human that you could hire as a co-worker.”

A “median human.” Nothing exemplifies the problems with this worldview more than this idea, which perfectly combines the mathiness, the arrogance, and the cluelessness in a single example.

The everything equation

As you might imagine, naive narcissist with a purely theoretical view of their fellow humans go about their days with a rather simple picture of things. For instance, they both like to turn even irreducibly complex human endeavors into simplistic equations.

The New York Times reports that:

Before making any kind of business decision, Mr. Bankman-Fried weighs the options in quantitative terms. “What’s the expected value?” he often asks co-workers, before assigning numbers to each possible outcome: A good result has positive EV; a bad one, negative EV.

Similarly, Altman proposed a theory of creativity on Twitter,

everything ‘creative’ is a remix of things that happened in the past, plus epsilon and times the quality of the feedback loop and the number of iterations. people think they should maximize epsilon but the trick is to maximize the other two.

Oh, right! That’s how creativity works. But he’s good at this sort of thing, as the New Yorker’s Tal Friend reported:

In a class that Altman taught at Stanford in 2014, he remarked that the formula for estimating a startup’s chance of success is “something like Idea times Product times Execution times Team times Luck, where Luck is a random number between zero and ten thousand.”

Needless to say, the illusion of math doesn’t illuminate anything, in any of these cases.

It does provide both men with a reason to stop thinking, though: here’s an equation, therefore this is all there is. No need to bother with the complexities of human creative processes, or the different sorts of goods that we can pursue, or the different possible explanations for a startup’s success or failure.

Just reduce it to a simplistic equation and move on.

Effective Altruism

Perhaps the most widely discussed trait the two Sams share is their passion for the blinkered moral philosophy known as Effective Altruism (EA), which reduces the world to a set of simplistic equations in order to provide a quantitative morality.

wrote an excellent essay about his own encounter with this philosophical worldview:And I wrote about the same movement a while back, too:

The EA movement itself reflects many of the traits we’ve discussed. It couldn’t care less about particular human beings—in fact, EA thinks it’s a flaw in your reasoning to love your family and friends more than people who live on the other side of the world, or more than people who won’t be alive till hundreds of years from now.

EA loves theoretical future people, because theoretical future people aren’t complicated and can be plugged into their simplistic equations.

Dickens satirized this worldview perfectly—150 years ago!—in his novel Bleak House. His character Mrs. Jellyby is so obsessed with saving people on some distant island that she neglects her own family, who live in squalor. IF SBF read (of course, he doesn’t believe in reading books), it’s easy to see him reading Bleak House and thinking Mrs. Jellyby was the heroine.

We become what we love

One of the intellectual godfathers of Effective Altruism was a brilliant Oxford philosopher named Derek Parfit. Parfit shared all the traits of Altman and Bankman-Frield outlined above, as this recent essay in the Hedgehog Review explains:

[Parfit's] adult life was replete with instances of actively ignoring obligations to friends and family—and to many others besides—for the sake of his philosophical writing. As his partner of thirty years and eventual wife, Janet Radcliffe Richards, put it after his death, “I can’t think of anything we did together that wasn’t what he wanted to do.” On the other hand, he would sometimes publicly weep at the thought of those who had lost their lives in the world wars or of unfinished Bach compositions.

The odd thing, as this essay explains, is that Parfit wasn’t always this way. Many people, including Parfit’s own wife, believed that Parfit had Asperger’s. (People told Altman the same thing; after initally reacting with anger, he realized they were possibly right.) People have thought that

The reason Parfit’s philosophical work was insensitive to obligations to kith and kin was that he himself was insensitive in this way. His philosophy reflects his antisocial behavior. Indeed, Parfit’s friends sometimes suggested that he may have had an autism spectrum disorder. However, as Edmonds notes, ASD is not something you develop later in life. And those who knew Parfit in his youth deny that he had any such condition at that time. His unfeeling alienation of friends and family seemed instead to grow with time—and after he had begun to deeply explore the moral cosmology he would eventually introduce in [his first book] Reasons and Persons. This should make us wonder if the causation here is not the other way around: The reason Parfit came to behave more impersonally toward those close to him was that he spent decades meditating on and arguing for the idea that we should behave more impersonally toward those close to us. His antisocial behavior reflected his philosophy. You might say he lived down to his principles.

We are what we love. We can love equations, and—lo and behold!—the world transforms into a set of simple equations. We can love people and nature, and the world becomes less simple, but a lot more delightful and beautiful, as well.

But in a world that increasingly worships math—and its “practical” counterpart, computer programming, don’t be surprised that people who claim to turn everything into a simple equation wind up with the media’s attention and adulation. After all, these people also become billionaires with ease. They flaunt the basic social norms the rest of us feel bound by. And they’re good at creating computer programs that promise us the world (don’t worry, they’ll figure out how to keep those promises later).

Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google, had this to say about Altman upon his firing:

Sam Altman is a hero of mine. He built a company from nothing to $90 Billion in value, and changed our collective world forever. I can't wait to see what he does next. I, and billions of people, will benefit from his future work- it's going to be simply incredible. Thank you, [Sam], for all you have done for all of us.

I think that the very idea of a single person “changing our collective world forever,” or doing anything that impacts “billions of people,” is the problem. Dictators impact the world on this scale—let’s stop pretending that it’s good for anyone else to aspire to it.